Latest

Press Release

04 February 2026

Statement by the Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator for Yemen on the resumption of UNHAS flights to Sana'a

Learn more

Video

03 February 2026

UNDP Yemen: Yemen is well known for producing sweet, premium watermelon

Learn more

Speech

30 January 2026

Statement by the Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator for Yemen on the Removal of UN Equipment and Assets to an Unknown Location by the Sana’a Authorities

Learn more

Latest

The Sustainable Development Goals in Yemen

The Sustainable Development Goals are a global call to action to end poverty, protect the earth’s environment and climate, and ensure that people everywhere can enjoy peace and prosperity. These are the goals the UN is working on in Yemen:

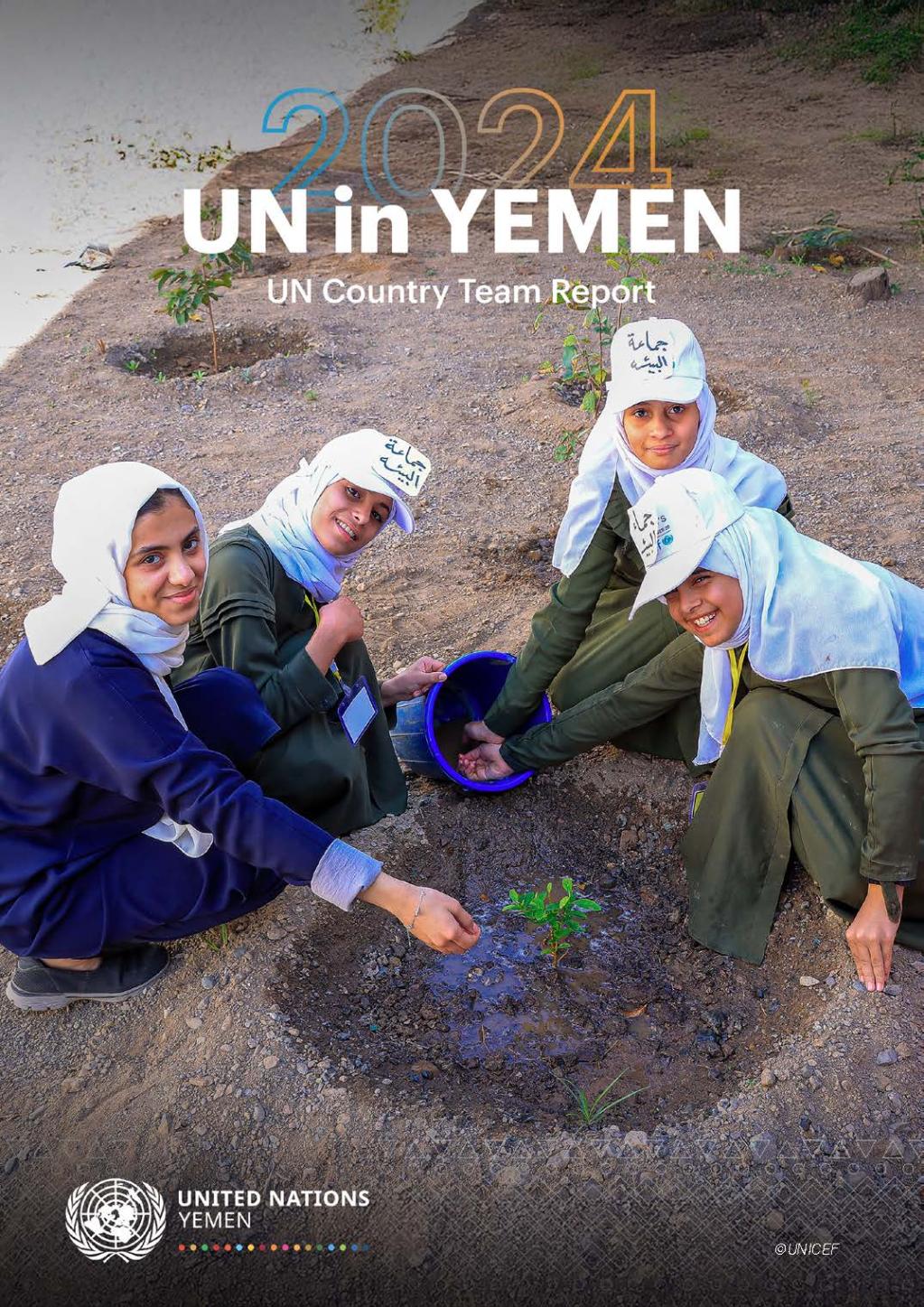

Publication

28 April 2025

UN Yemen Country Results Report 2024

This report highlights the resilience of the Yemeni people and the collaborative impact of the United Nations Country Team and its partners in 2024. Despite immense challenges, significant strides were made in delivering essential development support, strengthening local capacities, and fostering pathways towards stability.Understand how the UN addressed critical needs in food security, healthcare, education, and livelihoods, while strengthening governance and promoting inclusive solutions. Discover the importance of strategic partnerships, innovative approaches, and the unwavering commitment to sustainable development goals in the Yemeni context.Download the full report to learn more about the UN's activities, achievements, and ongoing dedication to supporting Yemen's journey towards a peaceful and prosperous future.

1 of 5

Press Release

05 September 2024

IOM Yemen: IOM Appeals for USD 13.3 Million to Help Hundreds of Thousands Affected by Yemen Floods

Yemen, 5 September – In response to the severe flooding and violent windstorms affecting nearly 562,000 people in Yemen, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) has launched a USD 13.3 million appeal to deliver urgent life-saving assistance. The unprecedented weather events have compounded the humanitarian crisis in the country, leaving thousands of internally displaced persons and host communities in dire need of assistance. “Yemen is facing yet another devastating chapter in its relentless crisis, exacerbated by the intersection of conflict and extreme weather events,” said Matt Huber, IOM Yemen’s Acting Chief of Mission. “IOM teams are on the ground, working around the clock to deliver immediate relief to families affected by this catastrophe. However, the scale of the destruction is staggering, and we urgently need additional funding to ensure that the most vulnerable are not left behind. We must act immediately to prevent further loss and alleviate the suffering of those impacted.” In recent months, torrential rains and flooding have destroyed homes, displaced thousands of families, and severely damaged critical infrastructure, including health centres, schools, and roads. Across multiple governorates, including Ibb, Sana’a, Ma’rib, Al Hodeidah, and Ta’iz, thousands of people have been left without shelter, clean water, or access to basic services, and scores of lives have been tragically lost. The storms have struck as the country grapples with a cholera outbreak and escalating food insecurity, further exacerbating the vulnerability of displaced families and strained health systems. As the harsh weather conditions are expected to continue, more households are at risk of displacement and exposure to disease outbreaks due to damaged water and health infrastructure. Ma’rib Governorate has been particularly hard-hit, with strong winds since 11 August severely damaging 73 displacement sites and affecting over 21,000 households. Public services, including electricity networks, have been severely affected, aggravating the crisis in one of Yemen’s most vulnerable regions. Urgent shelter repairs and cash assistance are needed, with healthcare services and sanitation infrastructure among the most immediate priorities. Since early August, floodwaters have damaged shelters, roads, water sources, and medical facilities, leaving over 15,000 families in Al Hodeidah and 11,000 in Ta’iz in desperate need of emergency support. These rains have not only led to tragic loss of life but have also wiped out entire communities’ belongings and means of survival. In response to this crisis, IOM is targeting 350,000 people with shelter, non-food items (NFI), cash-based interventions, health, camp coordination and camp management, and water, sanitation, and hygiene interventions. Distribution of water tanks, latrine repairs, and desludging efforts are ongoing in multiple sites, while health services are being expanded, with mobile teams currently treating over 100 individuals and referring critical cases to hospitals. IOM’s efforts are further supported by emergency response committees working tirelessly to register and verify affected households, relocate displaced families, and reduce the risks of further damage. However, the resources available are insufficient to cover the vast needs, with key gaps remaining, especially in the shelter and NFI sector. With no contingency stocks for essential relief items and the situation growing more critical by the day, immediate funding is necessary to address the most pressing needs on the ground. IOM stands ready to scale up its response but requires the necessary resources to do so. With further severe weather expected in the coming weeks and funding constraints, the Organization is urgently calling on the international community to support this appeal to continue providing lifesaving aid and address the overwhelming needs of those affected. To read the full appeal, please visit this page. For more information, please contact: In Yemen: Monica Chiriac, mchiriac@iom.int In Cairo: Joe Lowry, jlowry@iom.int In Geneva: Mohammedali Abunajela, mmabunajela@iom.int

1 of 5

Press Release

04 May 2023

Statement: Remarks at the pledging event for the FSO Safer operation co-hosted by the Netherlands and the United Kingdom

First, I want echo Achim’s thank you to the United Kingdom and the Netherlands for having organized this event.

And for contributing generously.

A third element that they both deserve credit for is recognizing early on the promise of a private-sector initiative to address the Safer which the Fahem Group and SMIT Salvage proposed in mid-2021 – a time when the previous UN plan to inspect the Safer was not moving.

The initiative called for a leading maritime salvage company to transfer the oil off the Safer and replace the decaying supertanker’s capacity.

That was the basis upon which the United Nations principals asked me to lead and coordinate UN system-wide efforts on the Safer, in September 2021.

In December 2021, United Nations senior management endorsed the UN-coordinated plan and asked UNDP to implement it, contingent upon donor funding.

In February 2021, I met with the Government of Yemen in Aden, which confirmed its support for the plan.

They have remained supportive ever since – as evidenced by a $5 million pledge that they made last year.

The Sana’a authorities had been favorable to the original initiative, but insisted that it be done under UN auspices.

In March 2022, they signed a memorandum of understanding with the UN that committed them to facilitating the operation.

A commitment that they continue to honor.

The agreement was also signed by myself with the Fahem Group, which has supported engagement in Sana’a on the initiative since 2021 on a voluntary basis.

By April 2022, the UN presented a draft operational plan to begin fundraising. The original budget for phase 1 and 2 was $144 million.

As Achim said, the Netherlands pledging event in The Hague last May brought in $33 million, which was a catalyst to move us to where we are today.

But finding funds to prevent a catastrophe proved far more difficult than finding money for a disaster.

In June, we launched a public crowdfunding campaign for the operation.

That has now brought in more than $250,000. More importantly, it captured media attention that galvanized further support for the plan.

In August, we received the first pledge from a private entity. $1.2 million from the HSA Group. The International Association of Oil and Gas Producers followed with a $10 million pledge and Trafigura Foundation with $1 million.

The private sector, we learned, was concerned about its liability linked to a contribution. UNDP, in particular, led the effort to resolve those issues of concern which gives us a basis for further private sector contributions.

By September last year, the UN met the target of $75 million to start the operation.

Unfortunately, even as UNDP was gearing up to begin, the cost of suitable replacement vessels surged, chiefly due to developments related to the war in Ukraine.

More money was also needed to start the initial phase because of the necessity to purchase a replacement vessel – also linked to the war in Ukraine as suitable vessels for lease were no longer available. The budget for the emergency phase – during which the oil will be transferred – is now $129 million. Most of the funding is now required up front in phase one. Now, the second phase only requires $19 million to complete the project.

So, the budget of $148 million is just $4 million more than was presented to donors a year ago.

Prior to today’s announcements, we had raised $99.6 million from member states, the private sector and the general public.

The general public has provided donations from $1 to $5,000.

The broad coalition working to prevent the catastrophe also includes environmental groups like Greenpeace and, in Yemen, Holm Akhdar.

Every part of the United Nations is involved, including the International Maritime Organization, the UN Environmental Progamme, and the World Food Progamme. The Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs is among those that have worked on the Safer file for years and has now ensured $20 million of bridging finance. That would need to be replenished by donor funding.

I also want to recognize the United States for playing a tireless role in mobilizing resources. It is among the top five donors, together with the Netherlands, Germany, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the United Kingdom.

On 9 March, UNDP’s Administrator took the bold decision to purchase the replacement vessel Nautica – before all of the operation was in place.

That is because UNDP recognized the extraordinary problem and understood that the cost of inaction is too great, as Achim outlined.

UNDP also contracted the Boskalis subsidiary SMIT Salvage, which played an enormously helpful role in developing the UN plan long before it had a contract.

With both the Nautica and the SMIT vessel Ndeavor en route to Djibouti, we expect the operation to start before the end of the month.

Therefore, I thank all donors for the generous support, and we look forward to further generous support.

But the risk of disaster remains.

I am forever thankful to the heroic skeleton crew aboard the Safer that continues to do all it can to keep that vessel together until we can organize this salvage operation.

None of us will heave a sigh of relief until the oil is transferred.

And we will all heave a final sigh of relief when the critical second phase is completed. This requires that the project is fully funded as described.

As everyone has said we are just one step away so lets take the final step.

Thank you.

1 of 5

Publication

26 October 2022

UNITED NATIONS YEMEN SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT COOPERATION FRAMEWORK 2022 – 2024

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

UN global reform has elevated the United Nations Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework (UNSDCF) to be “the most important instrument for planning and implementing UN development activities” in the country. It outlines the UN development system’s contributions to reach the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in an integrated way, with a commitment to leave no one behind, uphold human rights, Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment (GEWE), and other international standards and obligations. The UNSDCF seeks to address the humanitarian, development and peace challenges in Yemen in an environment where key public institutions are fragmented, no national strategy exists, and where there has been no national budget since 2014. The Yemen UNSDCF outlines the UN’s collective priorities and development objectives to be reached jointly in the next three years 2022-2024 as part of an ongoing and longer- term vision for resilience building and forging of a pathway to peace.

Yemen is a country in conflict. The priorities of this UNSDCF are derived from the analysis of the impacts of this ongoing crisis on the people of Yemen, and the needs and opportunities as outlined in the UN’s Common Country Analysis (CCA) conducted in 2021.

The UN has prioritized four pillars that resonate with the SDG priorities of people, peace, planet and prosperity that aim, as a matter of urgency, to improve people’s lives in Yemen and build resilience that is equitable, inclusive, people-centred, gender responsive and human rights based, through outcomes that: 1. Increase food security, improving livelihood options, and job creation 2. Preserve inclusive, effective and efficient national and local development systems strengthening 3. Drive inclusive economic structural transformation 4. Build social services, social protection, and inclusion for all

The theory of change is driven by an expectation that by 2024 the impact for all people of all ages in Yemen affected by conflict, forced displacement and living in poverty in all its dimensions will experience change in the quality of their lives. This will be possible through increased food security and nutrition, livelihood options and job creation; preserved national and local development and systems strengthening; inclusive economic structural transformation and the building of social services, social protection and inclusion for all. Food security and nutrition, and sustainable and resilient livelihoods and environmental stability will be realized through effective food production and diversified food and nutrition security; and through sustainable climate sensitive environmental management. Rights-based good governance and inclusive gender sensitive improved public services and rule of law will be possible as a result of accountable, inclusive and transparent institutions and systems, as well as the building of trusted justice systems. Increased income security and decent work for women, youth and vulnerable populations will be realised through micro and macro-economic development and job creation. Strengthened social protection and basic social support service delivery focused on support to marginalized groups, and strengthening women and youth leadership in decision making processes will be supported through the preservation of social protection and expanded and effective social assistance and basic services.

The UNSDCF prioritises the population groups in Yemen that have the highest risk of being left behind due to the impact of conflict; economic, social, geographic or political exclusion; and marginalisation. Enacting the central transformative principle of the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs, whilst challenging in the Yemen context, does provide the lens through which the UNSDCF targets the most vulnerable and prioritise Leaving No One Behind.

On the basis that some groups in Yemen bear the brunt of the conflict due to forced displacement, livelihood disruption, food insecurity, limited social safety nets, increased levels of poverty and poor-

quality housing, the CCA 2021 identifies the following population groups at the greatest risk of being left behind:

- Women and girls - 73 percent of those displaced in Yemen are women and girls, especially women of reproductive age and adolescent girls

- Children – 60 percent of those killed directly by conflict are children under five

- Youth and adolescents – an estimated 2 million school-age girls and boys are out of school as poverty, conflict, and lack of opportunities disrupt their education

- Internally displaced persons – more than 4 million IDPs with 172,000 newly displaced in 2020 and almost 160,000 in 2021

- Refugees, asylum seekers and migrants – Yemen hosts approximately 138,000 migrants and 140,000 refugees and asylum seekers

- Persons with disabilities – 4.5 million Yemenis have at least one disability

- Ethnic and religious minorities – It is estimated that Muhamasheen represent 10 percent of the population living in marginalised conditions

The UNSDCF is comprised of four chapters. Chapter One: explores Yemen’s progress towards the 2030 Agenda through a detailed analysis of the country context drawing on the 2021 CCA. Chapter Two: presents the theory of change generally and per outcome area. Chapter Three: outlines the UNSDCF’s implementation plan focused on the management structure, resources, links to country programming instruments and Yemen’s Business Operations Strategy. Chapter Four: highlights the process for CCA updates, Monitoring and Evaluation and Learning. The Results Framework presents the outcomes and key performance indicators for monitoring agreed targets utilizing verifiable data sets. Two annexes capture the legal basis for all UN entities engaged in the UNSDCF and the mandatory commitments to Harmonised Approaches to Cash Transfers (HACT)1.

The UNSDCF represents the UN’s understanding that continued engagement in Yemen requires an operational architecture under-pinned by the Business Operations Strategy (BOS) and an integrated set of achievable programming priorities. These two strategic approaches of the UN system strengthen and make more inclusive the country’s national and local governance structures, and mainstream the required responses to the economic and health consequences of COVID-19. They tackle food insecurity and nutrition as a matter of priority and integrate the promotion and advancement of gender equality and women’s and girl’s empowerment.

UN global reform has elevated the United Nations Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework (UNSDCF) to be “the most important instrument for planning and implementing UN development activities” in the country. It outlines the UN development system’s contributions to reach the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in an integrated way, with a commitment to leave no one behind, uphold human rights, Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment (GEWE), and other international standards and obligations. The UNSDCF seeks to address the humanitarian, development and peace challenges in Yemen in an environment where key public institutions are fragmented, no national strategy exists, and where there has been no national budget since 2014. The Yemen UNSDCF outlines the UN’s collective priorities and development objectives to be reached jointly in the next three years 2022-2024 as part of an ongoing and longer- term vision for resilience building and forging of a pathway to peace.

Yemen is a country in conflict. The priorities of this UNSDCF are derived from the analysis of the impacts of this ongoing crisis on the people of Yemen, and the needs and opportunities as outlined in the UN’s Common Country Analysis (CCA) conducted in 2021.

The UN has prioritized four pillars that resonate with the SDG priorities of people, peace, planet and prosperity that aim, as a matter of urgency, to improve people’s lives in Yemen and build resilience that is equitable, inclusive, people-centred, gender responsive and human rights based, through outcomes that: 1. Increase food security, improving livelihood options, and job creation 2. Preserve inclusive, effective and efficient national and local development systems strengthening 3. Drive inclusive economic structural transformation 4. Build social services, social protection, and inclusion for all

The theory of change is driven by an expectation that by 2024 the impact for all people of all ages in Yemen affected by conflict, forced displacement and living in poverty in all its dimensions will experience change in the quality of their lives. This will be possible through increased food security and nutrition, livelihood options and job creation; preserved national and local development and systems strengthening; inclusive economic structural transformation and the building of social services, social protection and inclusion for all. Food security and nutrition, and sustainable and resilient livelihoods and environmental stability will be realized through effective food production and diversified food and nutrition security; and through sustainable climate sensitive environmental management. Rights-based good governance and inclusive gender sensitive improved public services and rule of law will be possible as a result of accountable, inclusive and transparent institutions and systems, as well as the building of trusted justice systems. Increased income security and decent work for women, youth and vulnerable populations will be realised through micro and macro-economic development and job creation. Strengthened social protection and basic social support service delivery focused on support to marginalized groups, and strengthening women and youth leadership in decision making processes will be supported through the preservation of social protection and expanded and effective social assistance and basic services.

The UNSDCF prioritises the population groups in Yemen that have the highest risk of being left behind due to the impact of conflict; economic, social, geographic or political exclusion; and marginalisation. Enacting the central transformative principle of the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs, whilst challenging in the Yemen context, does provide the lens through which the UNSDCF targets the most vulnerable and prioritise Leaving No One Behind.

On the basis that some groups in Yemen bear the brunt of the conflict due to forced displacement, livelihood disruption, food insecurity, limited social safety nets, increased levels of poverty and poor-

quality housing, the CCA 2021 identifies the following population groups at the greatest risk of being left behind:

- Women and girls - 73 percent of those displaced in Yemen are women and girls, especially women of reproductive age and adolescent girls

- Children – 60 percent of those killed directly by conflict are children under five

- Youth and adolescents – an estimated 2 million school-age girls and boys are out of school as poverty, conflict, and lack of opportunities disrupt their education

- Internally displaced persons – more than 4 million IDPs with 172,000 newly displaced in 2020 and almost 160,000 in 2021

- Refugees, asylum seekers and migrants – Yemen hosts approximately 138,000 migrants and 140,000 refugees and asylum seekers

- Persons with disabilities – 4.5 million Yemenis have at least one disability

- Ethnic and religious minorities – It is estimated that Muhamasheen represent 10 percent of the population living in marginalised conditions

The UNSDCF is comprised of four chapters. Chapter One: explores Yemen’s progress towards the 2030 Agenda through a detailed analysis of the country context drawing on the 2021 CCA. Chapter Two: presents the theory of change generally and per outcome area. Chapter Three: outlines the UNSDCF’s implementation plan focused on the management structure, resources, links to country programming instruments and Yemen’s Business Operations Strategy. Chapter Four: highlights the process for CCA updates, Monitoring and Evaluation and Learning. The Results Framework presents the outcomes and key performance indicators for monitoring agreed targets utilizing verifiable data sets. Two annexes capture the legal basis for all UN entities engaged in the UNSDCF and the mandatory commitments to Harmonised Approaches to Cash Transfers (HACT)1.

The UNSDCF represents the UN’s understanding that continued engagement in Yemen requires an operational architecture under-pinned by the Business Operations Strategy (BOS) and an integrated set of achievable programming priorities. These two strategic approaches of the UN system strengthen and make more inclusive the country’s national and local governance structures, and mainstream the required responses to the economic and health consequences of COVID-19. They tackle food insecurity and nutrition as a matter of priority and integrate the promotion and advancement of gender equality and women’s and girl’s empowerment.

1 of 5

Press Release

15 August 2024

UNFPA/UNICEF Yemen: Life-saving aid critical as torrential rain sparks deadly floods across Yemen

Sana’a, 15 August 2024As relentless rain and catastrophic flooding in Yemen continue to exacerbate the suffering of families grappling with the impacts of poverty, hunger and protracted conflict, UNFPA, the United Nations Population Fund and UNICEF, the United Nations Children’s Fund, are delivering life-saving aid to some of the most vulnerable individuals through the Rapid Response Mechanism (RRM). With torrential rains forecast to continue into September, US$4.9 million is urgently needed to scale up the emergency response. Exceptionally heavy seasonal rains have caused flash floods in Yemen which are wreaking havoc in different parts of the country – the governorates of Al Hodeidah, Hajjah, Sa’ada, and Taizz are among the hardest-hit. Homes, shelters, and belongings have been swept away. Since early August, more than 180,000 people have been affected – over 50,000 people have been displaced in Al Hodeidah alone – a figure that is likely to rise in the coming days. Within 72 hours of the floods, over 80,000 people in flood-affected governorates had received emergency relief through the RRM, including ready to eat food rations, hygiene items, and women’s sanitary products. These items offer some immediate relief from the hardships caused by these catastrophic events. “The devastating floods have increased people’s needs, which are tremendous,” said Enshrah Ahmed, UNFPA Representative to Yemen. “Our RRM teams are working round the clock to provide immediate relief to affected families, but with rising needs and severe weather conditions forecasted, the coming weeks and months will be critical to ensuring affected families can pick themselves up and, at the very least, recover their lives.” In 2024, an estimated 82 percent of people supported through the RRM have been severely affected or displaced by climate-related shocks. As a result of the unseasonal levels of rain, the RRM cluster has had to spring into action, overstretching RRM teams, and depleting available supplies and resources. As needs continue to rise, RRM teams are struggling to reach affected families due to damaged roads, the erosion of landmines and unexploded ordnance from frontline to civilian areas. Items included in the RRM package are also in short supply. “The situation in the flooded areas is devastating. UNICEF and partners are on the ground providing urgently needed support to those impacted. The role of the Rapid Response Teams is critical in times of distress such as this one,” said Peter Hawkins, UNICEF Representative to Yemen.The RRM in Yemen was established in 2018 to provide a minimum package of immediate, critical life-saving assistance during human-made or natural disasters to newly displaced persons, and people in displacement sites or hard-to-reach areas, until the first line cluster response kicks in. The RRM ensures the distribution of immediate, ready-to-eat rations, basic hygiene kits provided by UNICEF, and women’s sanitary items provided by UNFPA, within 72 hours of a displacement alert. *** For more information, please contact UNFPA Taha Yaseen: Tel. +967 712 224090; yaseen@unfpa.org Lankani Sikurajapathy: Tel. +94773411614; sikurajapathy@unfpa.org UNICEF Kamal Al-Wazizah: Tel. +967 712 223 06; kalwazizah@unicef.org

1 of 5

Story

28 January 2026

UNFPA Yemen: From warehouses to women’s lives: How medical supplies are saving mothers in Yemen

Abyan and Al Dale' Governorates, Yemen In Yemen, where pregnancy and childbirth can quickly become life-threatening, a woman’s survival often depends on something she never sees: whether essential medicines are available when she needs them most. Behind every emergency intervention is a supply system working quietly in the background, ensuring that life-saving reproductive health supplies reach health facilities across the country.In Abyan and Al Dale’ governorates, reproductive health warehouses play a central role in keeping this system running. In Abyan, supplies are distributed to 169 health facilities across 11 districts. In Al Dale’, medicines from the warehouse serve between 3,000 and 4,000 women every month. Yet for years, poor infrastructure threatened their ability to function. Leaking roofs, frequent power outages and extreme heat compromised storage conditions, putting temperature-sensitive medicines such as oxytocin–an essential drug used to control bleeding during and after childbirth–at risk.“Parts of the roof started falling on us while we were working,” recalls Dr. Somaya Mohammed Ahmed, a UNFPA, United Nations Population Fund, Reproductive Health Supply Officer in Abyan. Supply chains behind life-saving careTo address these challenges, UNFPA, with funding from the Kingdom of the Netherlands through the UNFPA Supplies Partnership, and in collaboration with local partner Field Medical Foundation (FMF), supported the rehabilitation of reproductive health warehouses in both governorates. The renovations tackled long-standing structural damage, improved storage conditions and introduced reliable power solutions to protect critical medicines.In Al Dale’, warehouse manager Dr. Ali Abdullah Saleh describes the transformation. “Before, there was no proper lighting or cooling, and rainwater damaged the medicines. Now the warehouse is protected, the temperature is stable and supplies can be stored safely.” From storage to facilitiesThe impact of these improvements is felt far beyond the warehouse walls. By ensuring medicines are stored correctly and distributed on time, the strengthened supply chain supports health workers on the front lines—where shortages or delays can cost lives.At the Reproductive Health and Maternity Centre in Zinjibar District, Abyan Governorate–supported by UNFPA with local partner FMF–that reliability saved the life of Sajda Nasser, 32. Already weakened by a complicated pregnancy, Sajda began bleeding heavily while travelling back from a remote area. By the time she reached the health centre, she had lost her baby and was in shock and unconscious.“I don’t remember anything,” she says. “I only heard the doctors saying, ‘She died, she died.’” When medicines are available, women surviveSajda was given oxytocin to control the bleeding, along with intravenous fluids to stabilize her condition. The medicines were available on site and had been stored at the correct temperature, ensuring their effectiveness.“When medicines are available, we can respond quickly and save lives,” Midwife Waheba explains. “When they are not, families have to search outside the facility, and that delay can be fatal.” Most maternal deaths she witnesses at the centre, whether following childbirth or after a miscarriage, are caused by bleeding. Sajda survived. Today, she has regained her strength and plans to return to the centre for family planning services, which—like all care provided at the facility—are free of charge. “If this centre did not exist, I believe I would have died,” she says. In a country where around three women die every day from pregnancy- and childbirth-related causes, and where the majority of these deaths are preventable with timely access to quality care, investments in infrastructure are investments in women’s lives. By supporting the rehabilitation of reproductive health warehouses, funding from the Netherlands is helping to ensure that essential medicines reach health facilities safely and reliably—protecting mothers, strengthening health systems and saving lives.

1 of 5

Story

20 January 2026

(Near-verbatim) Transcript of the Press Conference by Julien Harneis, UN Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator for Yemen

Palais Des Nations – Geneva, 19 January 2026 Moderator (Alessandra)Good morning. Welcome. Sorry, for the waiting, and thank you very much for being with us at this press conference on the humanitarian situation in Yemen and the work of the UN. We have the great pleasure to have with us Julien Harneis, the UN Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator for Yemen. As usual, Mr. Harneis will deliver some introductory remarks, and then we will have time for questions and answers. I would also like to welcome the journalists who are currently online.

So, Julien, you have the floor first.

Julien HarneisYeah. Thank you. Thank you. Thank you very much, and- and thank you for your patience. I don’t get out of Yemen much, so it took me a little while to find the room.

I’ve just come from Aden, two days ago. I thought it was particularly important to meet with the media to talk about the situation there and to have an exchange with you. You are part of our world, and I really want to have a conversation.

Now, the context in Yemen is very, very concerning humanitarian-wise.

Last year, we had 19.5 million people in need, and the Humanitarian Response Plan was only 28% financed. We are expecting things to be much worse in 2026.

Why? The way that economic and political decisions are playing out, the situation of food insecurity is only getting worse across all parts of the country, but particularly on the Tihama, along the Red Sea.We’re seeing that playing out into malnutrition. And the health system, which has been supported by the United Nations with the World Bank for 10 years now—will see a major change: the health system is not going to be supported in the way it has been in the past.

That is going to have major consequences, because the government and the authorities in Sana’a do not have the capacity to support the health system—to finance the health system.

And therefore, in a country which has already seen the highest rates of measles in the world, and which has frequently had cholera epidemics, we’re going to be very vulnerable to epidemics across the country, but particularly in the north.

The other element which makes our work so much more difficult in the north is the detention of 73 UN colleagues. We have had 73 colleagues detained—the first in 2021, then in 2023, then in 2024, and then twice in 2025.

And with those detentions and the seizure of our offices, it has meant that the UN does not have the conditions for us to be able to work.

Personally, I’ve worked twice in Yemen—six years in total—before the start of the war and the beginning of the war, and then these last two years. I was personally part of setting up much of the humanitarian endeavour across the country. To see our humanitarian response so hobbled is terrifying.

I’m very worried for my colleagues, but above all I’m very worried for what this will mean for a humanitarian response for the Yemeni population that badly needs assistance.

Now we are working with the broader Humanitarian Country Team—INGOs and national NGOs—to see how other organizations can step up and do more to cover what the UN is doing. But there are some unique capacities that only UN agencies have, and only UN agencies have the scale of response that is required for a country where, for example, 2,300 primary healthcare systems are being supported by UN agencies.

No NGO has the capacity to support all of that. So, we’re going to have a very difficult time. We will, as a humanitarian community, do our best to restructure and reorganize to be able to do that, but in the current circumstances it is deeply challenging. And the obviously this is also in a broader situation of a very constrained funding environment.

So that’s the overview of the challenges—and maybe we get into questions. AlessandraAbsolutely. Thank you very much, Julien. We will now go to questions. I’ll start with the room. Robin, correspondent of AFP. Journalist (Robin, AFP)Good morning. Thank you. Do you feel that, with everything else going on in the world at the moment—Gaza, Ukraine, even Greenland—that Yemen and the humanitarian situation there is being totally overlooked?

And secondly, you spelled out the financial situation for 2025. For 2026, how many people are going to be in need of humanitarian aid? How many of them do you think you’ll be able to reach?

And what is the funding situation—how much money do you need, and how much do you think you’ll be able to get? Julien HarneisThank you.

Look—thanks for the question, Robin. It really depends on which media you’re looking at. As you can see it today, in this press conference, there are online connections from the Gulf region and the broader Middle East, and there is a lot of interest. In regional Arabic-language media, there is a lot of coverage of what is going on in areas under the control of the Government of Yemen, and more generally what goes in Yemen.

One of the constraints is that there is very little media that goes into areas under Sana’a. And 70% of the population is there – international media or regional media [I meant]. In the last two years, I can think of maybe one or two international media that have been there.

We as humanitarian organizations are constantly speaking out about the situation. We raise it every month. In the Security Council—OCHA—does a briefing on the humanitarian situation in Yemen. But international media is not engaging with Yemen in the way that I think is needed.

Now, obviously, on our side as well, we need to reach out more and discuss that. So yes, it’s definitely a challenge.

And it’s not just with the media, with member states who support the humanitarian response, we are looking to increase engagement with them.

A lot of the responses – for many years - have been funded by "Western governments" – I think we can describe them [as such], but obviously they are financially under pressure, and their budgets are coming down. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, the Emirates, and other Gulf member states have been generous, and we’re hoping engagement with them will bring greater attention to the humanitarian side, because there is obviously a lot of political attention.

So that is sort of the matter of attention. As I said earlier, 28% of funding is not good. About 688 million last year was the amount received.

It is the beginning of the year, so I don’t know how things will play out this year. But given the environment, I am very concerned. I have spoken to Tom Fletcher, the Emergency Relief Coordinator. Yemen is one of his priorities. It’s on his list, and he’s bringing that to member states and to the Inter-Agency Standing Committee.

We’re doing what we can to bring greater attention to this, but it’s going to be needed. And my fear is that we won’t hear about it until mortality and morbidity significantly increase this next year. Thank you. AlessandraThank you very much. Other questions in the room? John Zaracostas, France 24 and The Lancet. Journalist (John Zaracostas)Good morning. I was wondering if you could bring us up to speed from the retreat. What message did you get from the Secretary-General concerning Yemen? And what are your top three priorities given the limited funds coming in? Where will you focus? There’s a risk of famine and the health situation is dire—so what are the top three priorities in the first six months? Thank you. Julien HarneisThank you, John. The Secretary-General is personally engaged on Yemen—following up on the political situation in all parts of the country; on the humanitarian file; and personally involved in the matter of the detention of our colleagues.

He travelled to Muscat, Oman, last month to engage with the Sultan to bring out the condition and the fact that our colleagues were detained and how that is an impediment to the UN’s ability to work in the north.He is deeply concerned about the political situation—you will have seen, his statements and that, but also the statements of Hans Grundberg, the Special Envoy. And in tandem with the Emergency Relief Coordinator—given his past as head of one of the major UN humanitarian agencies, he is deeply worried about that too. So the Secretary-General is following in detail.In terms of priorities: first, it is a priority for Yemenis firstly, then is it is a priority for the Humanitarian Country Team. The focus has to be on public health and malnutrition, as well as food insecurity.Why? Because whilst the food insecurity is deeply worrying and we are expecting a degradation, it is not food insecurity that kills. Food insecurity contributes to malnutrition, but as does poor access to clean water, as does lack of access to health services, and socioeconomic conditions. When those things combined together, you get malnutrition—and that’s where you see mortality and morbidity, particularly affecting the [children] under-fives, and particularly children under the age of two.

So nutrition, public health, particularly at the primary healthcare level, and food insecurity come together and are our priorities across the country. AlessandraThank you very much. Uh, yes, Boris?

Journalist (Boris)Yes. Uh, Boris Engelson, a local freelancer. You alluded to the, attitude, the lack of information conveyed in the media. In, the current world, in crisis situations, there are places where we think, we feel we understand what's going on. In Gaza, most people think, rightly or wrongly, they understand what's going on. In some other places, it's a bit, we are not sure who are the good and bad guy. But in some countries, like Yemen, most people, even informed people, don't really understand what's going on. So among 10 people you report on Yemen or you, uh, address about Yemen, how many know, understand what's going on? Julien Harneis

Well, you know, I've been working in humanitarian conflicts and emergencies non-stop for 20 years - not as long as some colleagues, but you know, it's a long time. And, Yemen is, without doubt, the most complicated and complex, humanitarian situation I've ever worked in, and I would generally say if anybody tells you they know what's going on in Yemen, they are … well, I think they're bluffing.So, I think zero out of 10 people should know what's going on in Yemen because it is an extraordinarily complicated situation. You know, I've just seen the last month in Aden, we went through a situation where you had the government of Yemen in charge. Then over 48 hours, the Southern Transitional Council took over, the whole of the government of Yemen areas including, areas which they'd not been in forever, and then, four weeks later they had announced - in Riyadh - that they had dissolved. And now the government of Yemen has retaken those areas. But at the same time, we've got demonstrations in Aden, saying "No. we're still there." So, you know, that's just in the government of Yemen areas without looking at, , Sana'a. So, it is an extraordinarily complex situation. And of course, that's the challenge for humanitarians. The more complicated the situation, the tendency is for member states and, and, for people who could, give money is to go, "No, it's just too complicated, we don't understand it and there isn't a simple narrative, and therefore, without that simple narrative, it is more difficult to raise funds."The reality is, the simple narrative is children are dying and it's gonna get worse.For 10 years, the UN and humanitarian organizations were able to improve mortality and improve morbidity. But with the conjunction that we're seeing this year, that's not gonna be the case. That is the simple story; that's what everybody needs to understand. Thank you. Alessandra Thank you very much, Julian. Let me go to the platform. We have got Nick Hamilbruns, and then New York Times. Journalist (Nick Hamilbruns)Yeah. Good morning. Thank you for taking my question. In the last couple of years, it looked as if there might be some kind of, patching up or agreement between Sana'a and, and Saudi Arabia. We've kind of lost sight of where that is. And I'm just wondering if you see any progress on that particular front. And secondly, you alluded to the problems with the STC. What is the state of that sort of particular conflict? How bad... how much is that impacting on humanitarian assistance and, to what extent .. is there sort of a homegrown desire for separation in the South? Or is that something that's being driven by, external partners, parties? Thank you. Julien HarneisThank you very much, Nick. I'll not answer the majority of your questions because it is an area that goes into the mandate of Hans Grundberg [SG Special Envoy for Yemen] on the political side as the Special Envoy, which he's uniquely placed to talk about. I work on the humanitarian and the development file. So, I'll sort of stick to my area of knowledge and competence.

What I can say is that the fact that the parties to the conflict have not been able to find a solution is what’s driving the increase from 19.5 million to 21 million people in need this year. It’s not active fighting; it’s not massive displacement; it’s not bombing, but it is the collapse of the economy; it is the ports, which have been heavily damaged in the last year; it is the fact that the airports are no longer operating; it is the disruption of essential services—health, education, and all of those things which create this worsening situation.

So, in the absence of political solutions, it is impossible for humanitarians to deal with this. We can take the edge of it; we can save lives; but we cannot stop the underlying dynamic that is creating all these needs.

In terms of the consequences in Government of Yemen areas …you know I’ve travelled all over Yemen. There are many parts of Yemen where you would go to and you'd think that you were in a country that has development challenges, but not a conflict.

The difficulty of the political challenges the country is going through at the moment means that, instead of focusing on development—instead of governments and local authorities being able to focus on improving electricity supplies; improving access to jobs; getting Yemenis employed; improving the healthcare system—instead of that, leaders of the countries in all parts are understandably focused on the political challenges.

There have been announcements that they will be working - supported by member states, particularly Saudi Arabia - to address that. But obviously it takes your eye off the ball. So, the political crisis - or the political challenges, I should say- has an immediate and direct impact on the lack of development and therefore feeds into increased humanitarian needs unnecessarily. AlessandraThank you very much, Julien. Yes, Robin—follow-up? Journalist (Robin, AFP)Thank you. The negotiations to free UN colleagues who are being detained—do you see any glimmers of light in that process? And do you see any signs that the parties to the conflict understand the level of damage that does to the UN’s ability to deliver humanitarian aid in the field? Julien HarneisYes. Thank you. I talk to the families a lot, as do the representatives [of UN agencies]. It’s terrible for them. Some families haven’t seen their loved ones in five years. They don’t know the conditions of detention. They don’t know where they are. They don’t know if they’re going to be sentenced to death in the coming days.So, the families are suffering, and – more broadly - it’s terrifying across all humanitarians who live or work in the north, because you just don’t know what’s going to happen to you next, and you don’t understand why, why did this happen?

You know, we’ve been working in the north for 10 years. We’ve been working in Yemen since the ’60s, but we’ve been working since the beginning of the conflict. We’ve been there, operating, making a huge contribution.

And then suddenly, in the last couple of years, this breakdown - and inexplicably so - that has a terrifying effect on the humanitarian workers more generally, which, in itself, is debilitating.Obviously, the detention of our colleagues comes within a broader context. There are also INGO staff who’ve been detained. Staff working for certain embassies have been detained, activists, people engaged in politics in different ways, people from the government.

Nobody talks about them. Nobody talks about them and who’s paying for their salaries. So, the detention is a much broader challenge across society. There are some detentions in the Government of Yemen areas, but nothing of the scale of what we see in the north.

So, it is a challenge directly for the humanitarians, but it’s more broadly a challenge for the Yemeni society that – I believe - from a human rights perspective, merits much more attention.Now, as I noted earlier, the Secretary-General has met with the Sultan. He has raised this with the Government of Saudi Arabia, with the Government of Iran, and with many member states of the region – himself personally, at all levels. Hans Grundberg has also done this—he’s constantly circling around the region. And we have a colleague working purely on the detainee file who is engaged.

Member states understand the challenge and express sympathy, but there are so many concerns that they find it difficult to apply the appropriate engagement to address this.

And of course, the other thing is that we’ve seen the situation in Yemen—it’s very intractable situation. If you look at what happened on the Red Sea and the other elements of the conflict: member states have attempted to put pressure on the authorities in Sana’a, and it has been very challenging.

So, it’s a really difficult issue to resolve. We need to keep at it for many years to come, and we do need greater support from member states. Thank you. AlessandraThank you very much, Julien. Let me see if there are other questions in the room. John—go ahead. Journalist (John Zaracostas)Coming back to the link between access to clean water and disease: as you know, quite a few water facilities were bombed. How many of these have been repaired and are producing clean water in urban and other areas? What percentage of the population would be roughly having access to clean water? Thank you. Julien HarneisThank you, John. The broader challenge for access to clean water is not so much physical damage caused by bombing campaigns, because the access to water in Yemen is very dispersed. You have borewells every couple of hundred meters in certain areas.

There are two challenges Yemen faces on water—and this is true across all of Yemen.

One is that with population increase, climate change, and a population that uses more water per capita than in the past, the water table in most urban areas—most major cities—is dropping. For example, in Sana’a some borewells go down to 1,000 meters and more.

So, you have a huge challenge about access to water because of those underlying situations - nothing to do with the conflict.Now, unlike countries where water is available five or ten meters below ground level, or surface water is available. What that means you need power. You need power to bring up the water—and that means diesel or you need big solar systems.And the economic challenges, the damage to the harbour, and the fact that the UN is unable to work on increasing the availability of solar and on increasing the capacity of diesel – delivering diesel – in order to bring up the water—are producing a massive constraint on water.

So that is another huge challenge for all parts of the country, but particularly the north. We’re looking, as humanitarians, to see how this can be resolved, but it is deeply challenging. Thank you. AlessandraAnd we have a request for follow-up from the New York Times. Nick? Journalist (Nick, New York Times)Thank you. The United States made it clear when it was providing $2 billion for Tom Fletcher the other day that Yemen was not on their list of potential beneficiaries. I am wondering, what’s your sense – from the discussions you've had so far on this year's appeal- of who is lining up to produce support? Is that mainly going to be European countries for the UN system? Or is the reality that the people most likely to provide funding for projects in Yemen are basically shunning the UN system and doing it bilaterally? Julien HarneisWhat I think—without wanting to throw flowers at Tom, the Emergency Relief Coordinator, I think the negotiation of the two billion for pooled funds is an extraordinary achievement, and it demonstrates a trust in the UN and in the mechanism of pooled funds mechanisms.

So that does not suggest they are shunning him. You don’t give two billion dollars to somebody you’re shunning. Or if you do, I’d like to be shunned as well.

So, there is clearly an engagement from the United States. But at the same time, you can understand why the United States would have great difficulty providing humanitarian funds for Yemen specifically.

Last year there was an active conflict- I'm not quite sure what the appropriate designation of it is, but Ansar Allah was firing missiles at the US Navy, and the US Navy was firing back. And there are employees of the United States who are detained. In those circumstances, it’s extraordinary that the United States did provide as much assistance as they did.

For many years the US was the biggest donor to the humanitarian response in Yemen. That’s no longer the case. I am hoping that at least in parts of Yemen the US government will come back to fund, and that’s important because they are—or have been—the world’s biggest humanitarian donor.

The top three donors in Yemen in recent years have been the United States, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, and the United Kingdom.

I am hoping that we will see even more support from the Gulf countries. A humanitarian crisis in Yemen is a risk to the Arabian Peninsula: Cholera crosses borders. Measles crosses borders. Polio crosses borders. And we’ve seen that in the past, particularly with cholera. So, as a community, worldwide, we need to provide humanitarian support, but I am particularly hoping that we will get great support from Gulf member states.

I’ve recently been invited to an event in Riyadh to contribute to a discussion on the Global Humanitarian Overview, precisely because King Salman Relief was so interested in the situation of Yemen. So, there is a great deal of interest there, and I think we need to work above all with those member states. Thank you. AlessandraThank you very much, Julien. Oh—John, sorry, I didn’t see you. Go ahead.Journalist (John Zaracostas)A final question—coming back to funding: roughly what percentage of funds donated by member states are earmarked, and how many give you more space to work? In other words, non-earmarked. Julien HarneisIn a highly charged, complex emergency like Yemen, most funds are directed either thematically or geographically or have constraints and limitations to ensure the money is spent in certain ways.So, there is very little in the way that funding is provided to UN agencies or NGOs where you can broadly spend it as you will. I don’t know precisely how you would describe that as earmarked or not.We do have a Yemen Humanitarian Fund, which has been very successful. 66% of the funding goes to local NGOs; 33% goes to women-led organizations. And those funds are always allocated based on the highest needs. And I think that links to the success of Tom [Fletcher] in securing the allocation towards pooled funds. Pooled funds is an excellent instrument precisely to address the most pressing needs in any particular country. Julien Harneis

We’re at the end, right? Can I say one thing? Alessandra

Of course you can. Julien Harneis (closing)

Thank you. I just wanted to appreciate the engagement and the importance of the press corps in engaging on this subject. We need to be looking a greater deal on what is going on in Yemen. I also want to note that some excellent work provided by local and regional analysts - I won’t embarrass them by naming them today - but there is some really solid work being done by those experts, but it’s not finding its way through to a broader public.

And I really hope that, together, we can get the message through about the great risks to Yemenis in this coming year, and the fact that we can, together, we can prevent an increase in mortality and morbidity, but it will be very challenging. Thank you. Alessandra (closing)Thank you, Julien. I really hope our colleagues, journalists here and on the platform – which are quite numerous - will listen to your appeal. We really invite you to continue keeping us abreast, whether you – and thank you very much for coming and speaking with journalists – or through your colleagues in the field Jean and others that can intervene in our press briefings from afar. We want to keep Yemen’s dire situation at the attention of journalists.

So thank you very much to everyone for following this press conference. Thanks to Julien for coming and speaking to the Geneva press corps. Have a nice day and a nice week, and I’ll see you tomorrow for the briefing. Julien Harneis

Yes. Thank you. Julien Harneis

Thank you so much.

So, Julien, you have the floor first.

Julien HarneisYeah. Thank you. Thank you. Thank you very much, and- and thank you for your patience. I don’t get out of Yemen much, so it took me a little while to find the room.

I’ve just come from Aden, two days ago. I thought it was particularly important to meet with the media to talk about the situation there and to have an exchange with you. You are part of our world, and I really want to have a conversation.

Now, the context in Yemen is very, very concerning humanitarian-wise.

Last year, we had 19.5 million people in need, and the Humanitarian Response Plan was only 28% financed. We are expecting things to be much worse in 2026.

Why? The way that economic and political decisions are playing out, the situation of food insecurity is only getting worse across all parts of the country, but particularly on the Tihama, along the Red Sea.We’re seeing that playing out into malnutrition. And the health system, which has been supported by the United Nations with the World Bank for 10 years now—will see a major change: the health system is not going to be supported in the way it has been in the past.

That is going to have major consequences, because the government and the authorities in Sana’a do not have the capacity to support the health system—to finance the health system.

And therefore, in a country which has already seen the highest rates of measles in the world, and which has frequently had cholera epidemics, we’re going to be very vulnerable to epidemics across the country, but particularly in the north.

The other element which makes our work so much more difficult in the north is the detention of 73 UN colleagues. We have had 73 colleagues detained—the first in 2021, then in 2023, then in 2024, and then twice in 2025.

And with those detentions and the seizure of our offices, it has meant that the UN does not have the conditions for us to be able to work.

Personally, I’ve worked twice in Yemen—six years in total—before the start of the war and the beginning of the war, and then these last two years. I was personally part of setting up much of the humanitarian endeavour across the country. To see our humanitarian response so hobbled is terrifying.

I’m very worried for my colleagues, but above all I’m very worried for what this will mean for a humanitarian response for the Yemeni population that badly needs assistance.

Now we are working with the broader Humanitarian Country Team—INGOs and national NGOs—to see how other organizations can step up and do more to cover what the UN is doing. But there are some unique capacities that only UN agencies have, and only UN agencies have the scale of response that is required for a country where, for example, 2,300 primary healthcare systems are being supported by UN agencies.

No NGO has the capacity to support all of that. So, we’re going to have a very difficult time. We will, as a humanitarian community, do our best to restructure and reorganize to be able to do that, but in the current circumstances it is deeply challenging. And the obviously this is also in a broader situation of a very constrained funding environment.

So that’s the overview of the challenges—and maybe we get into questions. AlessandraAbsolutely. Thank you very much, Julien. We will now go to questions. I’ll start with the room. Robin, correspondent of AFP. Journalist (Robin, AFP)Good morning. Thank you. Do you feel that, with everything else going on in the world at the moment—Gaza, Ukraine, even Greenland—that Yemen and the humanitarian situation there is being totally overlooked?

And secondly, you spelled out the financial situation for 2025. For 2026, how many people are going to be in need of humanitarian aid? How many of them do you think you’ll be able to reach?

And what is the funding situation—how much money do you need, and how much do you think you’ll be able to get? Julien HarneisThank you.

Look—thanks for the question, Robin. It really depends on which media you’re looking at. As you can see it today, in this press conference, there are online connections from the Gulf region and the broader Middle East, and there is a lot of interest. In regional Arabic-language media, there is a lot of coverage of what is going on in areas under the control of the Government of Yemen, and more generally what goes in Yemen.

One of the constraints is that there is very little media that goes into areas under Sana’a. And 70% of the population is there – international media or regional media [I meant]. In the last two years, I can think of maybe one or two international media that have been there.

We as humanitarian organizations are constantly speaking out about the situation. We raise it every month. In the Security Council—OCHA—does a briefing on the humanitarian situation in Yemen. But international media is not engaging with Yemen in the way that I think is needed.

Now, obviously, on our side as well, we need to reach out more and discuss that. So yes, it’s definitely a challenge.

And it’s not just with the media, with member states who support the humanitarian response, we are looking to increase engagement with them.

A lot of the responses – for many years - have been funded by "Western governments" – I think we can describe them [as such], but obviously they are financially under pressure, and their budgets are coming down. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, the Emirates, and other Gulf member states have been generous, and we’re hoping engagement with them will bring greater attention to the humanitarian side, because there is obviously a lot of political attention.

So that is sort of the matter of attention. As I said earlier, 28% of funding is not good. About 688 million last year was the amount received.

It is the beginning of the year, so I don’t know how things will play out this year. But given the environment, I am very concerned. I have spoken to Tom Fletcher, the Emergency Relief Coordinator. Yemen is one of his priorities. It’s on his list, and he’s bringing that to member states and to the Inter-Agency Standing Committee.

We’re doing what we can to bring greater attention to this, but it’s going to be needed. And my fear is that we won’t hear about it until mortality and morbidity significantly increase this next year. Thank you. AlessandraThank you very much. Other questions in the room? John Zaracostas, France 24 and The Lancet. Journalist (John Zaracostas)Good morning. I was wondering if you could bring us up to speed from the retreat. What message did you get from the Secretary-General concerning Yemen? And what are your top three priorities given the limited funds coming in? Where will you focus? There’s a risk of famine and the health situation is dire—so what are the top three priorities in the first six months? Thank you. Julien HarneisThank you, John. The Secretary-General is personally engaged on Yemen—following up on the political situation in all parts of the country; on the humanitarian file; and personally involved in the matter of the detention of our colleagues.

He travelled to Muscat, Oman, last month to engage with the Sultan to bring out the condition and the fact that our colleagues were detained and how that is an impediment to the UN’s ability to work in the north.He is deeply concerned about the political situation—you will have seen, his statements and that, but also the statements of Hans Grundberg, the Special Envoy. And in tandem with the Emergency Relief Coordinator—given his past as head of one of the major UN humanitarian agencies, he is deeply worried about that too. So the Secretary-General is following in detail.In terms of priorities: first, it is a priority for Yemenis firstly, then is it is a priority for the Humanitarian Country Team. The focus has to be on public health and malnutrition, as well as food insecurity.Why? Because whilst the food insecurity is deeply worrying and we are expecting a degradation, it is not food insecurity that kills. Food insecurity contributes to malnutrition, but as does poor access to clean water, as does lack of access to health services, and socioeconomic conditions. When those things combined together, you get malnutrition—and that’s where you see mortality and morbidity, particularly affecting the [children] under-fives, and particularly children under the age of two.

So nutrition, public health, particularly at the primary healthcare level, and food insecurity come together and are our priorities across the country. AlessandraThank you very much. Uh, yes, Boris?

Journalist (Boris)Yes. Uh, Boris Engelson, a local freelancer. You alluded to the, attitude, the lack of information conveyed in the media. In, the current world, in crisis situations, there are places where we think, we feel we understand what's going on. In Gaza, most people think, rightly or wrongly, they understand what's going on. In some other places, it's a bit, we are not sure who are the good and bad guy. But in some countries, like Yemen, most people, even informed people, don't really understand what's going on. So among 10 people you report on Yemen or you, uh, address about Yemen, how many know, understand what's going on? Julien Harneis

Well, you know, I've been working in humanitarian conflicts and emergencies non-stop for 20 years - not as long as some colleagues, but you know, it's a long time. And, Yemen is, without doubt, the most complicated and complex, humanitarian situation I've ever worked in, and I would generally say if anybody tells you they know what's going on in Yemen, they are … well, I think they're bluffing.So, I think zero out of 10 people should know what's going on in Yemen because it is an extraordinarily complicated situation. You know, I've just seen the last month in Aden, we went through a situation where you had the government of Yemen in charge. Then over 48 hours, the Southern Transitional Council took over, the whole of the government of Yemen areas including, areas which they'd not been in forever, and then, four weeks later they had announced - in Riyadh - that they had dissolved. And now the government of Yemen has retaken those areas. But at the same time, we've got demonstrations in Aden, saying "No. we're still there." So, you know, that's just in the government of Yemen areas without looking at, , Sana'a. So, it is an extraordinarily complex situation. And of course, that's the challenge for humanitarians. The more complicated the situation, the tendency is for member states and, and, for people who could, give money is to go, "No, it's just too complicated, we don't understand it and there isn't a simple narrative, and therefore, without that simple narrative, it is more difficult to raise funds."The reality is, the simple narrative is children are dying and it's gonna get worse.For 10 years, the UN and humanitarian organizations were able to improve mortality and improve morbidity. But with the conjunction that we're seeing this year, that's not gonna be the case. That is the simple story; that's what everybody needs to understand. Thank you. Alessandra Thank you very much, Julian. Let me go to the platform. We have got Nick Hamilbruns, and then New York Times. Journalist (Nick Hamilbruns)Yeah. Good morning. Thank you for taking my question. In the last couple of years, it looked as if there might be some kind of, patching up or agreement between Sana'a and, and Saudi Arabia. We've kind of lost sight of where that is. And I'm just wondering if you see any progress on that particular front. And secondly, you alluded to the problems with the STC. What is the state of that sort of particular conflict? How bad... how much is that impacting on humanitarian assistance and, to what extent .. is there sort of a homegrown desire for separation in the South? Or is that something that's being driven by, external partners, parties? Thank you. Julien HarneisThank you very much, Nick. I'll not answer the majority of your questions because it is an area that goes into the mandate of Hans Grundberg [SG Special Envoy for Yemen] on the political side as the Special Envoy, which he's uniquely placed to talk about. I work on the humanitarian and the development file. So, I'll sort of stick to my area of knowledge and competence.

What I can say is that the fact that the parties to the conflict have not been able to find a solution is what’s driving the increase from 19.5 million to 21 million people in need this year. It’s not active fighting; it’s not massive displacement; it’s not bombing, but it is the collapse of the economy; it is the ports, which have been heavily damaged in the last year; it is the fact that the airports are no longer operating; it is the disruption of essential services—health, education, and all of those things which create this worsening situation.

So, in the absence of political solutions, it is impossible for humanitarians to deal with this. We can take the edge of it; we can save lives; but we cannot stop the underlying dynamic that is creating all these needs.

In terms of the consequences in Government of Yemen areas …you know I’ve travelled all over Yemen. There are many parts of Yemen where you would go to and you'd think that you were in a country that has development challenges, but not a conflict.

The difficulty of the political challenges the country is going through at the moment means that, instead of focusing on development—instead of governments and local authorities being able to focus on improving electricity supplies; improving access to jobs; getting Yemenis employed; improving the healthcare system—instead of that, leaders of the countries in all parts are understandably focused on the political challenges.

There have been announcements that they will be working - supported by member states, particularly Saudi Arabia - to address that. But obviously it takes your eye off the ball. So, the political crisis - or the political challenges, I should say- has an immediate and direct impact on the lack of development and therefore feeds into increased humanitarian needs unnecessarily. AlessandraThank you very much, Julien. Yes, Robin—follow-up? Journalist (Robin, AFP)Thank you. The negotiations to free UN colleagues who are being detained—do you see any glimmers of light in that process? And do you see any signs that the parties to the conflict understand the level of damage that does to the UN’s ability to deliver humanitarian aid in the field? Julien HarneisYes. Thank you. I talk to the families a lot, as do the representatives [of UN agencies]. It’s terrible for them. Some families haven’t seen their loved ones in five years. They don’t know the conditions of detention. They don’t know where they are. They don’t know if they’re going to be sentenced to death in the coming days.So, the families are suffering, and – more broadly - it’s terrifying across all humanitarians who live or work in the north, because you just don’t know what’s going to happen to you next, and you don’t understand why, why did this happen?

You know, we’ve been working in the north for 10 years. We’ve been working in Yemen since the ’60s, but we’ve been working since the beginning of the conflict. We’ve been there, operating, making a huge contribution.

And then suddenly, in the last couple of years, this breakdown - and inexplicably so - that has a terrifying effect on the humanitarian workers more generally, which, in itself, is debilitating.Obviously, the detention of our colleagues comes within a broader context. There are also INGO staff who’ve been detained. Staff working for certain embassies have been detained, activists, people engaged in politics in different ways, people from the government.

Nobody talks about them. Nobody talks about them and who’s paying for their salaries. So, the detention is a much broader challenge across society. There are some detentions in the Government of Yemen areas, but nothing of the scale of what we see in the north.

So, it is a challenge directly for the humanitarians, but it’s more broadly a challenge for the Yemeni society that – I believe - from a human rights perspective, merits much more attention.Now, as I noted earlier, the Secretary-General has met with the Sultan. He has raised this with the Government of Saudi Arabia, with the Government of Iran, and with many member states of the region – himself personally, at all levels. Hans Grundberg has also done this—he’s constantly circling around the region. And we have a colleague working purely on the detainee file who is engaged.

Member states understand the challenge and express sympathy, but there are so many concerns that they find it difficult to apply the appropriate engagement to address this.

And of course, the other thing is that we’ve seen the situation in Yemen—it’s very intractable situation. If you look at what happened on the Red Sea and the other elements of the conflict: member states have attempted to put pressure on the authorities in Sana’a, and it has been very challenging.

So, it’s a really difficult issue to resolve. We need to keep at it for many years to come, and we do need greater support from member states. Thank you. AlessandraThank you very much, Julien. Let me see if there are other questions in the room. John—go ahead. Journalist (John Zaracostas)Coming back to the link between access to clean water and disease: as you know, quite a few water facilities were bombed. How many of these have been repaired and are producing clean water in urban and other areas? What percentage of the population would be roughly having access to clean water? Thank you. Julien HarneisThank you, John. The broader challenge for access to clean water is not so much physical damage caused by bombing campaigns, because the access to water in Yemen is very dispersed. You have borewells every couple of hundred meters in certain areas.

There are two challenges Yemen faces on water—and this is true across all of Yemen.

One is that with population increase, climate change, and a population that uses more water per capita than in the past, the water table in most urban areas—most major cities—is dropping. For example, in Sana’a some borewells go down to 1,000 meters and more.

So, you have a huge challenge about access to water because of those underlying situations - nothing to do with the conflict.Now, unlike countries where water is available five or ten meters below ground level, or surface water is available. What that means you need power. You need power to bring up the water—and that means diesel or you need big solar systems.And the economic challenges, the damage to the harbour, and the fact that the UN is unable to work on increasing the availability of solar and on increasing the capacity of diesel – delivering diesel – in order to bring up the water—are producing a massive constraint on water.

So that is another huge challenge for all parts of the country, but particularly the north. We’re looking, as humanitarians, to see how this can be resolved, but it is deeply challenging. Thank you. AlessandraAnd we have a request for follow-up from the New York Times. Nick? Journalist (Nick, New York Times)Thank you. The United States made it clear when it was providing $2 billion for Tom Fletcher the other day that Yemen was not on their list of potential beneficiaries. I am wondering, what’s your sense – from the discussions you've had so far on this year's appeal- of who is lining up to produce support? Is that mainly going to be European countries for the UN system? Or is the reality that the people most likely to provide funding for projects in Yemen are basically shunning the UN system and doing it bilaterally? Julien HarneisWhat I think—without wanting to throw flowers at Tom, the Emergency Relief Coordinator, I think the negotiation of the two billion for pooled funds is an extraordinary achievement, and it demonstrates a trust in the UN and in the mechanism of pooled funds mechanisms.

So that does not suggest they are shunning him. You don’t give two billion dollars to somebody you’re shunning. Or if you do, I’d like to be shunned as well.

So, there is clearly an engagement from the United States. But at the same time, you can understand why the United States would have great difficulty providing humanitarian funds for Yemen specifically.

Last year there was an active conflict- I'm not quite sure what the appropriate designation of it is, but Ansar Allah was firing missiles at the US Navy, and the US Navy was firing back. And there are employees of the United States who are detained. In those circumstances, it’s extraordinary that the United States did provide as much assistance as they did.

For many years the US was the biggest donor to the humanitarian response in Yemen. That’s no longer the case. I am hoping that at least in parts of Yemen the US government will come back to fund, and that’s important because they are—or have been—the world’s biggest humanitarian donor.

The top three donors in Yemen in recent years have been the United States, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, and the United Kingdom.