Desert Locusts: Building Yemen’s Capacity to Prevent New Swarms

The first thing that comes to mind when we think of the desert locust is destruction.

Traveling in swarms that can number in the billions, or even trillions, and spread over large swathes of land, this small insect causes catastrophic damage to pasture and to crops. A small swarm can in one day eat the same amount of food as 35,000 people or damage 100 tonnes of crops across a square kilometre of fields. Locust invasions are a major threat to food security and, in worst-case scenarios, lead to famine and displacement. So, when developing swarms hit Yemen toward the end of 2019, the food security of almost 30 million people was at risk.

With conflict eroding their resilience and diminishing the country’s financing for public services, Yemenis were unprepared for this fierce insect. Prior to the conflict, Yemen had an efficient national monitoring and control program but when the latest local invasion struck, Yemen was short of pesticide and equipment to apply it along with vehicles to carry out “survey and control” field operations. People in rural areas were affected most by the locust invasion. The locusts destroyed plants and fodder on agricultural land, leading to crop and animal losses, eroding incomes, and adding to the burden rural, vulnerable households already felt from the conflict.

Farmers, livestock breeders and nomads living in infested areas were at risk of having their livelihoods annihilated. Most had never seen anything like it in their lifetime and did not have the know-how nor technical capacity to save their crops. COVID-19 added another layer of stress and prevented most farmers and herders threatened by the locusts from finding alternative incomes in nearby towns, as they would have usually done. Urgent action was needed to control the locust swarms which were fast spreading beyond its borders, eventually becoming the main source of swarms that invaded the Greater Horn of Africa and West Asia. Yemen’s regional importance in battling locust infestations cannot be overstated. Yemen is one of the key desert locust breeding grounds in the region, where swarms develop in several locations throughout the year and then disperse across the country and region, affecting the food security and livelihoods of tens of millions of people across East Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia.

Taming the threat

Using funding from international partners—Canada, Belgium, Saudi Arabia, the United Kingdom, and the FAO’s Technical Cooperation Programme fund—the United Nations’ Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) worked with Yemeni authorities in 2020 to combat locust swarms. Desert locust surveillance and control operations were set up in key breeding grounds around Yemen to lessen local infestation and prevent swarms from invading neighboring countries. Extensive training and capacity building by the Ministry of Agriculture meant locusts were controlled in some infested areas. By the end of 2020, FAO-led locust control operations in Yemen had treated 48,082 hectares of agricultural land and surveyed a total area almost ten times that size.

World Bank funding provided through the Locust Response Project supported surveillance and control operations and strengthened Yemen’s preparedness for future infestations. From the beginning of the winter breeding season in 2020/2021, we began noticing promising signs that desert locusts were in retreat. Surveillance, spraying, and control operations in breeding grounds helped wipe out large numbers of the insect—good news for the millions of agriculture-dependent households trying to survive the effects of the protracted conflict. So far, the 2021 agricultural season has experienced no significant locust outbreaks.

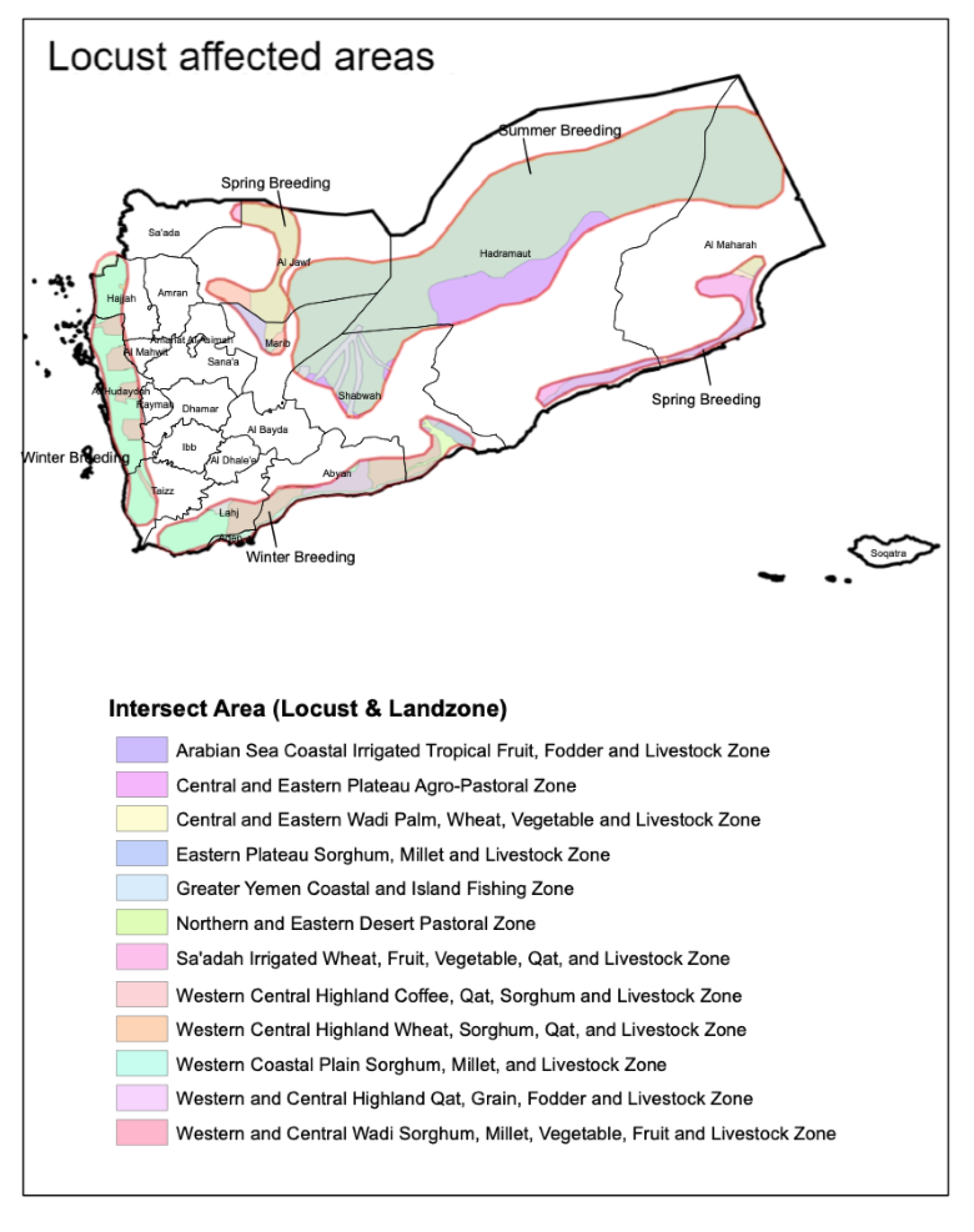

Drawing on its more than 70 years of experience fighting desert locusts, the FAO expects swarms to continue breeding in Yemen's interior (figure 1 shows desert locust breeding areas and seasons in Yemen). So, while the battle against the desert locust swarms of 2020 may have been won, the war against locusts is expected to intensify given Yemen’s vulnerability to climate change. Climate change has triggered the strongest alterations in water temperature in the Indian Ocean in 60 years. Warmer seas create more extreme rainfall as well as stronger and more frequent cyclones, providing ideal conditions for locusts to hatch, breed, and disperse widely. That’s why it is so critical to strengthen Yemen’s capacity to tackle desert locust swarms in the future.

The most important part of strengthening Yemen’s desert locust response is rebuilding the country’s national network of Desert Locust Control Centers (DLCC) in key breeding areas. The World Bank-financed project will support the establishment/refurbishment, equipping and capacity building of the DLCC network. This network includes early warning and response systems to support the prevention and rapid response to new and existing locust infestation, thereby limiting in-country and cross-border spread of the swarms. The integrated warning and response system will have the most up-to-date information to trigger informed desert locust ground and/or aerial operations for swarm control. The system will also monitor meteorological data, which will enable response mechanisms for other disasters and adverse climate events. Monitoring will also help increase the sharing of reliable climate-smart pest management information in communities. This integrated system is based on an application installed on mobile devices to enter data in the field on the locust situation, monitor and maintain the necessary equipment and logistics, and track the quantity and quality of pesticide stocks. The warning and response system will be connected to the FAO’s Desert Locust Information Service, which receives and analyses data from locust-affected countries, so that it can issue warnings and alerts, promote collaboration among countries and keep the global community informed on locust developments.

The importance of maintaining operational surveillance and control capacity in Yemen cannot be overstated, particularly as any uncontrolled breeding in the future could once again affect the Greater Horn of Africa, as it did in 2020, and the entire Middle East and West Asia.